Almost 3.7 million people in the UK have been diagnosed with diabetes and it’s estimated a further one million are currently undiagnosed (1).

Type 2 diabetes is the most common diabetes in adults, affecting around 90% of those with the disease – and it’s on the rise.

The number of people diagnosed with diabetes in the UK has doubled in the last 20 years, largely due to the rise in obesity.

It occurs when lifestyle factors affect the functioning of the pancreas, the gland concerned with the control of blood sugar.

On the other hand, Type 1 diabetes occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks and kills certain cells in the pancreas; it’s generally thought of as a disease which is irreversible.

Type 1 diabetes affects people both in childhood and as adults.

Hormones and Blood Sugar Control

Our body cells use glucose for energy and this is transported around the body in the bloodstream.

The level of blood glucose must be kept within very narrow margins otherwise, if sugar is too high, it can damage our body cells.

If blood sugar drops too low, the brain becomes starved of oxygen.

Even a slight drop in blood sugar can make us jittery, anxious and stressed.

The process of controlling blood sugar is a clever system involving the two hormones, insulin and glucagon.

When the level of sugar in the blood increases, cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, release insulin.

This causes cells all over the body to take sugar out of the blood to use as energy.

As a result the blood sugar drops once more.

Glucagon is released in response to low blood sugar levels by the alpha cells of the pancreas.

This serves to increase blood sugar levels by releasing stored energy from the liver and the muscles.

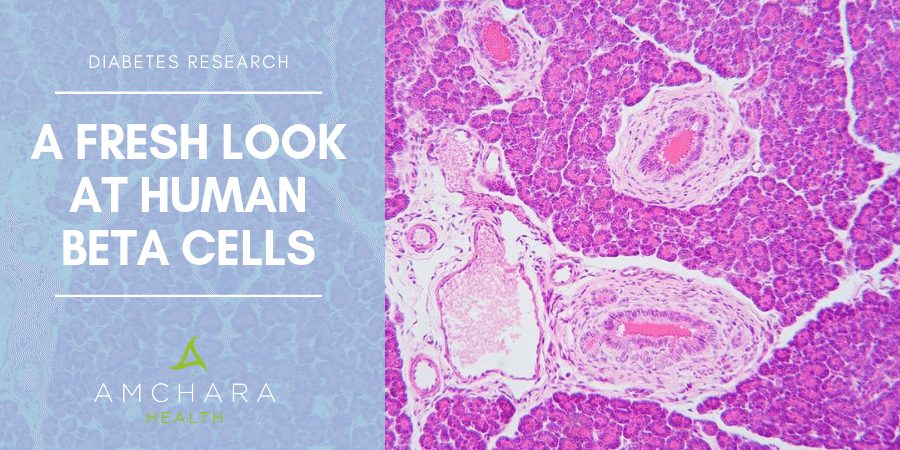

Pancreas alpha and beta cells are concentrated in an area of the pancreas called the islets of Langerhans.

Beta cells are the most abundant of the cells in this area.

Also found here are delta cells which secrete a hormone called somatostatin, which we’ll discover more about later.

Beta Cell Loss and Diabetes

Unfortunately what can happen over time is the beta cells in the pancreas become damaged or die.

This means insufficient insulin is released and sugar builds up in the blood because it can’t get into the cells of the body to be used for fuel.

Too much sugar in the blood can lead to damage to blood vessels, vision problems, heart disease and stroke, kidney disease and nerve problems.

We know nutrition, lifestyle, obesity and inflammation can all contribute towards the development of Type 2 diabetes, but interesting recent research has focused on what can affect the functioning of the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

In both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, beta cell functioning is lost, but for different reasons.

In Type 1 diabetes, the cells are attacked by the body’s own immune system and die.

In Type 2 diabetes, the beta cells either die or fail to produce sufficient insulin because of problems with their functioning.

The beta cells may be affected by their environment – chemicals secreted by other cells, for example.

Obesity seems to make more beta cells die (2).

One study found alpha cells, as well as producing glucagon, also secrete a messenger substance called glutamate, which appeared to kill beta cells (3).

Other research has found still more factors which can damage beta cells, such as high blood glucose and free fatty acids in the blood.

Can Beta Cells be Restored?

It’s not surprising, then, that diabetes research has concentrated on finding factors which could restore beta cell functioning.

Some success has already been seen with a 4-day fasting-mimicking diet which was able to reverse beta cell failure (4).

However, one recent study, using only human cells rather than animal subjects, has found that rather than simply being destroyed, beta cells may change their function when Type 2 diabetes develops.

The researchers looked at human tissue from people with diabetes and discovered some of the beta cells produced somatostatin – normally secreted by delta cells.

This is a hormone which is produced by a broad range of body tissues and exists in two forms.

The type made by pancreas delta cells can block the release of other hormones such as glucagon but of particular relevance for diabetics, it can also block the secretion of insulin.

The researchers found people who suffered from either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes had more delta cells in their pancreas than normal, suggesting their beta cells had changed into delta cells.

What’s more it appears this change may actually be reversible, something which wasn’t previously expected (5).

Human vs Animal Studies

The other notable factor about this study is it used only human cells.

It’s thought the change of the beta cells into delta cells does not occur in rodents.

Previous studies using mice had found the beta cells tended to change into alpha cells instead, which resulted in elevated glucagon, and this was believed to be a factor in the development of diabetes.

In previous research, strategies for increasing the replication of beta cells or their transformation from other cells have been successful in animal studies but not in humans (6).

In fact, other research has found human and rodent pancreas tissue has Islets of Langerhans with different structural characteristics (7).

So, this study gives us a more accurate picture of what happens in the human pancreas when diabetes develops.

Why do Beta Cells Change?

The researchers of the above study tried to find out why the cells changed from beta to delta cells.

Cells in the pancreas respond to a communication system which sends messages via RNA (ribonucleic acid) from the cell’s DNA to tell proteins how to behave. This system appears to change in the case of diabetes.

The researchers looked at the genes which are involved in deciding which type of RNA message is made.

They discovered around 25% of genes from people with Type 2 diabetes showed alterations to the usual message pattern when compared to people without diabetes.

The researchers were even able to turn the delta cells back to beta cells in the laboratory, so restoring their ability to produce insulin.

This was done by returning their environment to normal – in other words, reducing blood sugar – or by administering chemicals to restore the regulator genes which in turn normalise the RNA messages.

What’s more, the results also have implications for those suffering from Type 1 diabetes.

Recently, scientists discovered Type 1 diabetes sufferers do still retain a certain amount of cells capable of producing insulin, but the environment produced by diabetes is toxic to these cells or can inhibit their activity.

If research can discover factors which could protect these cells, they could be encouraged to make insulin.

Conclusion

Type 2 diabetes is considered to be primarily caused by a combination of lifestyle, envrionmental and genetic factors.

We’re dedicated to providing you with both insightful information and evidence-based content, all orientated towards the Personalised Health approach.

Did you find this article useful?

Do you have any suggestions for managing Type 2 diabetes?

We would love to hear from you.

READ THIS NEXT: